全球父母在這數碼時代面對的挑戰

2018-02-07

© UNICEF/UN08733/Ashley Gilbertson

兩名伊拉克男童在奧地利維也納的難民處理中心興奮地使用手機,他們的媽媽在輪候申請庇護。

全球越來越多兒童使用互聯網,大部分是透過手機上網。不少家長感到自己的能力、角色和權威受到挑戰。然而,兒童透過上網可以獲得有用的知識和彌補與家長缺失的聯繫。究竟家長應何從選擇?

數碼教育鴻溝

在高收入國家進行的研究表明,越來越多父母從過往的管束教育,如禁止孩子使用互聯網或會在孩子闖禍後責備他們,變為越來越多父母採用啟發方式教育孩子,如分享自身的上網經驗及指導孩子使用私隱設置、諮詢服務和對網上內容及行為進行批判性評價。這種教育方式的轉變不但因為家長在使用數碼產品時獲得經驗和知識,還有賴政府、兒童福利機構和相關持分者為提高家長意識和鼓勵他們參與而付出的成果。

© UNICEF/UN0147080/Shehzad Noorani

同伴倡導者在肯尼亞基蘇木的尼亞蘭大地區透過電話與朋友交流,他們的組織Sauti Skika由青年人管理和營運,為青年愛滋病病毒感染者發聲,確保大眾能聆聽他們的聲音。

可是在中等和低收入國家,家長似乎依然傾向管束教育。在這些國家的文化中,管教子女的方式更專制(尤其針對女兒)。缺乏資源亦是另一原因,焦慮的父母會認為採取管束教育是保護孩子的唯一方法。另外,社會未把兒童當成積極公民或數碼公民也是原因之一。

很多發展中國家的兒童由親戚如祖父母撫養。在非洲、部分拉丁美洲地區和加勒比海地區,很多兒童只與父母其中一方生活,甚至不與父母一起生活。鑒於移民、疾病、父母早逝等因素,令父母和監護人沒有足夠資源和時間培養兒童的數碼技能。學校同樣也面對困難,發展中國家的學校入學率低、學生與老師人數比例過高、擁擠的課室和未經培訓的老師司空見慣。因此,成年人無法提供支援和教導兒童安全使用網絡、及在他們需要時提供幫助。

最新研究結果

了解家長和兒童在數碼時代面對的限制,是尋求解決辦法的第一步,這樣才能將風險減至最低,同時幫助孩子最大程度地獲得機會。我們在進行「全球兒童在綫」的研究,追蹤身處數碼時代的家長和兒童的行為和經歷。研究由聯合國兒童基金會(UNICEF)英諾森提研究中心、倫敦政治經濟學院和「歐盟兒童在綫」與全球各地研究人員和UNICEF地區辦公室展開的跨國研究。研究目的是在兒童權益框架的指導下,尋找確切方案引發兒童對使用網絡進行討論和為政策落實提供參考。

![[RELEASE OBTAINED] (Left) Gaiela Vlad, 17, uses her phone to speak with her mother at the dinner table at the home of her foster mother Tatiana Gribincea (right) in the village of Porumbeni on the outskirts of Moldova, Monday 16 October 2017. The dinner was traditional Moldovan foods, washed down with home made wine and pressed berry juice for the children. During dinner, Gaiella called her mother Svetlana - usually she video chats with her mother during dinner, but tonight the internet connection failed them, and Svetlana chatted on speaker with her daughter, son, husband and friends. Moldova gained independence from the former USSR in 1991, and since then has regularly ranked as one of the worlds unhappiest countries. Moldova is the poorest nation in Europe - according to the World Bank, the average per capita G.D.P. in 2016 was $1,900. The country’s economy is reliant on agriculture and foreign remittances: at least one quarter of the population live and work aoad, sending pay home to support their families. With so many people leaving the country to find gainful employment, Moldova is officially the fastest shrinking country on earth. Gaiela Vlad is a seventeen-year-old student living in the village of Porumbeni, 10 miles (16 kilometres) from Chisinau, Moldova. In 2006, Gaiella’s mother Svetlana decided she needed to travel aoad in order to earn a higher income and provide her children with better opportunities. Before leaving Moldova, Svetlana worked in a printing house earning 2000 lei (USD$120) a month, and was unable to support her family financially. She now works as a nurse at a German nursing home for the elderly. The night before Svetlana left, the family gathered at the dinner table and Gaiela’s father, who works as a police detective and like all public employees in Moldova is very poorly remunerated, made a speech before they began: “Enjoy this, it’s the last time you’re going to eat this well until she comes home.”](/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/UN0139548_r-1024x683.jpg)

© UNICEF/UN0139548/Gilbertson V

2017年10月16日,在摩爾多瓦首都奇西瑙郊外的博魯貝尼村,17歲的布里埃拉‧加比‧弗蘭德(圖左)在養母塔蒂亞娜‧格裏賓西(圖右)家中用手機與在國外工作的媽媽聊天。

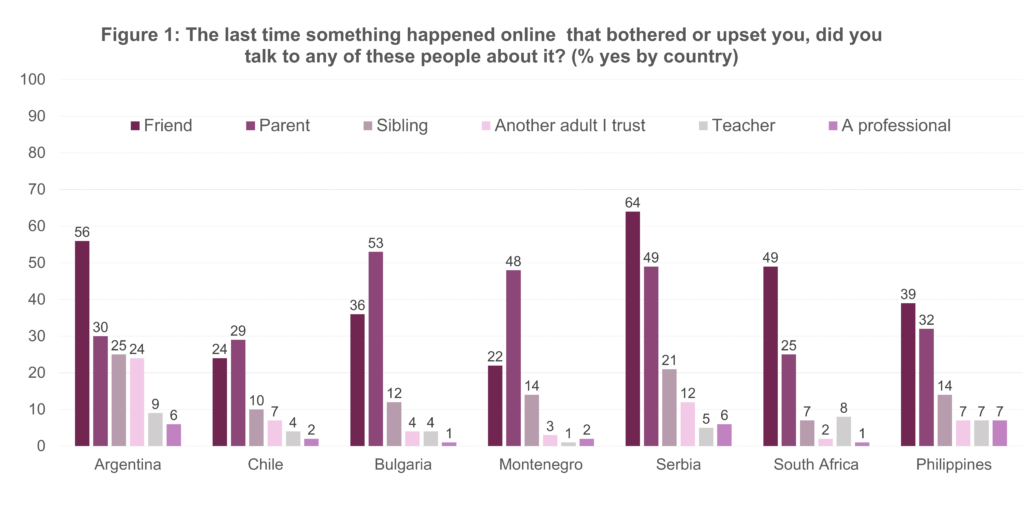

除了訪問兒童的上網活動、次數、時間、技能、風險外,我們還試圖了解兒童在網絡上遇到負面事情時會向誰尋求幫助。令人驚訝的是,來自7個國家的大部分兒童首先會選擇朋友,其次是家長,很少人選擇老師或其他專業人士。這對家長是好消息,儘管根據保加利亞、黑山共和國和南非的調查顯示,家長的數碼技能水平僅相當於14歲兒童的水平,但兒童表示相信父母有能力支持和教導自己。

令人關注的是,與其它國家和地區相比,來自歐洲國家的兒童在網絡遇到負面事情時會偏向告訴父母。這或能反映大部分歐洲家長採用啟發教育方式而非管束教育。顯然,南半球的家長需要更多資源支持他們學習和教育孩子的方法。更令人擔憂的,是兒童明顯對老師和專業人士缺乏信任。我們很想知道,是否專業人士無法達到我們期望的水平,以及兒童對專業人士能否提供正確建議感到沒有信心。

註釋:受訪對象除阿根廷13至17歲兒童外,還包括其餘國家9至17歲兒童。塞爾維亞和菲律賓進行的是小規模試點調查;南非採用抽樣調查;其餘國家樣本皆有全國代表性。有關更多細節,敬請參考:www.globalkidsonline.net/results

如何鼓勵家長支持兒童?

如果家長保護孩子的主要方式是管束教育,那儘管能保護孩子的安全,但孩子卻無法透過網絡獲得學習機會。管束教育可能剝奪兒童學習數碼技能的機會,而這些技能會幫助他們面對和處理危險。我們應為家長提供甚麼建議?身處數碼時代的他們需要扮演甚麼角色?他們需要具備甚麼能力?我們在科技大爆炸前所採用的教育原則如今是否適用?

世界衞生組織在2007年制定關鍵指標的框架,用來衡量家長職責和教育方式為青少年成長帶來的正面影響:

- 親子關係(父母與孩子應建立正面穩定的關係)

- 行為控制(在相互信任的基礎上監管和指導孩子)

- 尊重孩子,尤其是青少年

- 樹立良好的榜樣(孩子會模仿家長的言行)

- 物質支持和身心保護(來自家長和社區)

10年過去,這框架仍適用於現今的數碼時代。以樹立良好榜樣為例:若家長整天亦機不離手,試問孩子又怎會不仿效呢?若家長採用管束教育,那孩子如何懂得尊重他人?最理想的是,家長能自信地運用自身、文化的資源,在迎接關於孩子使用網絡挑戰時才能積極應對。同樣,在家長因擔心孩子受到危險而決定採取管束教育時,也該意識到孩子從中學習的技能或對未來至關重要,如學習、獲取訊息、工作、社交活動等。這雖然很困難,但家長必須從中尋求平衡,因為這很大程度上取決兒童的成長環境。

網絡越來越普及,並成為日常生活的一部分,家長也漸成為網絡原居民。為了自身和孩子,他們也想了解網絡更多,以及它究竟能為生活帶來甚麼。所以,無論是政府、學校、社會還是整個網絡行業,所有相關持分者都應給家長最大支持,讓他們能在這數碼時代好好幫助兒童成長和學習。