Building memories under siege

2016-06-24

©UNICEF/Syria/2016/Rural Damascus Scenes of destruction where children live and spend their days inside Harasta.

On 18 May 2016, UNICEF delivered humanitarian assistance for the first time in four years to the besieged city of Harasta in Rural Damascus. Just 11km from Damascus, 17,000 people were trapped under siege in the once bustling commercial and industrial hub of east Ghouta.

During the summer of 2013, I crossed the Homs-Damascus highway for the first time since the conflict erupted in Syria. The viant Harasta I knew on the way to Damascus was turned to an atrocious scene of destruction from which I hid by closing the car window shade when I passed by.

Harasta has been under siege since 2012. But finally, our UNICEF team managed to reach almost 5,000 children and their families with medical, educational and recreational materials to at least ease some of the children’s suffering.

The drive to Harasta, a 15-munte trip before the war, took us three and a half hours. For two of those hours, we waited for permission to enter. Our convoy was smooth compared to others, where colleagues had to wait at checkpoints for over ten hours.

For the first time, I couldn’t close the window shade as we drove inside Harasta. Scenes of children living and playing among the destruction struck me.

Children showered us with questions the minute we left the cars: “How did you arrive here? What did you ing us? Are you coming from Damascus?” A woman said: “Excuse us, they’re very excited. It’s been so long since they met someone coming from outside Ghouta.”

©UNICEF/Syria/2016/Rural Damascus Harasta: More scenes of destruction from the besieged town.

©UNICEF/Syria/2016/Rural Damascus Part of the road Aya and 250 other girls, some with children, pass every day to go to school.

The ongoing conflict is severely impacting all forms of civilian life in Harasta. As we talked with women, education came up as a major concern.

“I am terrified of sending my children to school,” one woman told us. “I have three children, two of them are old enough to go to school but I don’t send them because I am afraid they will be killed in an attack.”

Eagerly, an 8-year-old girl grabbed my sleeve: “I should be in the third grade but we had to leave our house last year and I missed the second grade,” she said, “I love school so much and I want to get back to it. I feel so bored at home”.

While taking photos, I overheard Aya, 13, telling her friend about the mission’s participants: “Look how lucky they are. All educated!” When I looked at her she told me: “I love learning. I want to become a lawyer to end up all the suffering we are experiencing.”

As we passed by the devastation to visit Aya’s school, we also saw a destroyed playground. “Children have no place to play and there’s no power for TV where they can watch cartoons just like any other child. They are growing up knowing nothing but war.” A man told us. “We need to educate them; otherwise, they will become a problem to the whole world when they grow up.”

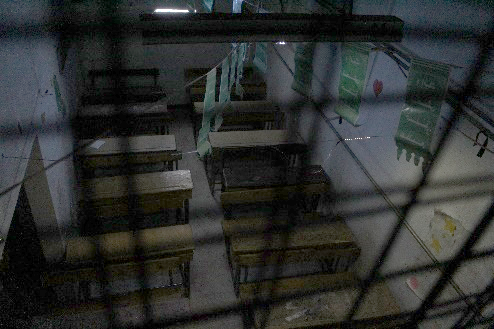

Only lit with dim LED lights, almost all the dark and damp classrooms, as well as the playground of the school Aya* attends with 250 other girls, operate underground. “We try our best to attract children to come to school although we barely have three hours of teaching a day; as we have to end the school day before 10am when shelling begins,” said the local Education Officer.

“One of our problems is that textbooks are becoming so old and worn out,” he added.

There are 20 married girls under the age of 18 attending classes at Aya’s school, some of them with children. The school is doing all it can to make education accessible for married girls. “We advocate against early marriage. At school, we have a kindergarten for babies of both teachers and married students,” said the Education Officer.

A 17-year-old girl we met married for the first time at age 14, was widowed shortly after and is now about to be divorced from her second marriage. One of her two children died. “I used to live with my other. My father is detained and my mother is married to another man. I got married for my safety,” she said. I asked her, “Do you go to school?” She said no.

Tough financial conditions have forced many children to work. Some of them have part-time jobs after school; others have left school for good, such as Mustafa* who works at a sweet shop for seven or eight hours a day. “I can’t go to school. I have a mother and five sisters and my father is dead. I need the money.” Just like any other child, Mustafa dreams about the future, “I want to become a doctor,” he said.

The Education Officer said, “There are so many children who’ve dropped out of school. We are doing our best to educate them through mosques or remedial classes during summer.”

©UNICEF/Syria/2016/Rural Damascus Only lighted with dim led lights, almost all the dark and damp classrooms as well as the playground of the school where Aya goes, along with other 250 girls, operate underground.

Life is impossible without hope. The children’s tiny, yet huge, dreams of becoming doctors or teachers – the little girl who insists she will become a lawyer – are the comforts that keep them motivated and aspiring to change.

In normal life, such dreams are natural. The lives of these children are not normal. They walk through destruction to reach school, they miraculously evade shells and many of them watched their friends and loved ones die right in front their eyes. Positive change will only come about by supporting the education and life skills of these children so they can contribute to society and rebuild a more stable and prosperous Syria. That day should come soon.

*Names were changed to protect children’s identities