Challenges of parental responsibility in the digital age: a global perspective

2018-02-07

© UNICEF/UN08733/Ashley Gilbertson

Two boys from Iraq laugh while using their cellular phones as they wait with their mother at a refugee processing centre in Vienna, Austria, where their family is applying for asylum.

Children everywhere are gaining access to the internet – most often via a mobile phone. In many places, too, parents are feeling challenged in their competence, role and authority. Distinctively, internet access is inging children access also to valued sources of knowledge and connection that their parents may lack. How are parents responding?

A digital parenting divide

Research in high income countries points to a shift away from restrictive forms of parental mediation such as banning the technology or telling their children off when a problem occurs. Instead, it seems parents are increasingly using enabling forms of mediation such as sharing some online experiences with their children and guiding them in the use of privacy settings, advice services and critical evaluation of online content and behaviour. This shift is influenced by parents’ own growing experience with and expertise in using digital media. It’s also the outcome of several years’ worth of multi-stakeholder efforts to raise parental awareness and encourage their engagement, often led by governments and child welfare organisations.

© UNICEF/UN0147080/Shehzad Noorani

Peer advocates communicate with their friends on phone in Nyalenda neighbourhood in the city of Kisumu, Kenya. Their organization, Sauti Skika, is an initiative for and by young people living with HIV, to ensure the voices of young people and adolescents living with HIV are heard.

But in middle and low income countries, it seems that parents favour restrictive mediation. This is partly because some cultures are more authoritarian in their parenting style (especially in relation to daughters). It’s partly because, in the absence of supportive resources, anxious parents feel their only recourse is to protect their children by limiting their access. It’s also because the wider public debate has yet to emace a conception of children as active citizens and, therefore now, also as digital citizens.

Even talking of parents – a common target of awareness-raising actions in the global North – is not straightforward as many children in developing countries are being ought up by relatives, often grandparents. For example, in Africa and, to a lesser extent in Latin America and the Caribbean, children are much more likely to live with either one or neither of their parents than children in other regions. Factors such as migration, illness, parental death often mean that parents and caregivers are left with few resources and insufficient time to help children with their digital skills. Schools are also challenged: in the least developed countries school attendance is low, pupil/teacher ratios are high, and overcrowded classrooms and untrained teachers are commonplace. It seems fair to conclude that in many countries, children lack a supportive and/or informed adult in their lives who can teach them to navigate the internet safely, or offer support when needed.

"…the wider public debate has yet to emace a conception of children as active citizens and, therefore now, also as digital citizens."

New research findings

Understanding the real constraints families and children face in the digital world is the first step towards finding effective strategies that both parents and children can use to maximise opportunities and minimise risks. We are currently tracking the activities and experiences of children and parents in the digital age as part of our research project Global Kids Online – a multinational research collaboration of the UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), and the EU Kids Online network in partnership with researchers and UNICEF country offices from all over the world. Working within a child rights framework, the aim is to generate robust evidence that can stimulate debate and inform policy and practice regarding children’s internet use in diverse countries.

![[RELEASE OBTAINED] (Left) Gaiela Vlad, 17, uses her phone to speak with her mother at the dinner table at the home of her foster mother Tatiana Gribincea (right) in the village of Porumbeni on the outskirts of Moldova, Monday 16 October 2017. The dinner was traditional Moldovan foods, washed down with home made wine and pressed berry juice for the children. During dinner, Gaiella called her mother Svetlana - usually she video chats with her mother during dinner, but tonight the internet connection failed them, and Svetlana chatted on speaker with her daughter, son, husband and friends. Moldova gained independence from the former USSR in 1991, and since then has regularly ranked as one of the worlds unhappiest countries. Moldova is the poorest nation in Europe - according to the World Bank, the average per capita G.D.P. in 2016 was $1,900. The country’s economy is reliant on agriculture and foreign remittances: at least one quarter of the population live and work aoad, sending pay home to support their families. With so many people leaving the country to find gainful employment, Moldova is officially the fastest shrinking country on earth. Gaiela Vlad is a seventeen-year-old student living in the village of Porumbeni, 10 miles (16 kilometres) from Chisinau, Moldova. In 2006, Gaiella’s mother Svetlana decided she needed to travel aoad in order to earn a higher income and provide her children with better opportunities. Before leaving Moldova, Svetlana worked in a printing house earning 2000 lei (USD$120) a month, and was unable to support her family financially. She now works as a nurse at a German nursing home for the elderly. The night before Svetlana left, the family gathered at the dinner table and Gaiela’s father, who works as a police detective and like all public employees in Moldova is very poorly remunerated, made a speech before they began: “Enjoy this, it’s the last time you’re going to eat this well until she comes home.”](/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/UN0139548_r-1024x683.jpg)

© UNICEF/UN0139548/Gilbertson V

Gaiela Vlad, 17, (Left) uses her phone to speak with her mother at the dinner table at the home of her foster mother Tatiana Gribincea (right) in the village of Porumbeni on the outskirts of Chisinau in Moldova, Monday 16 October 2017. Her biological mother has gone aoad to find employment.

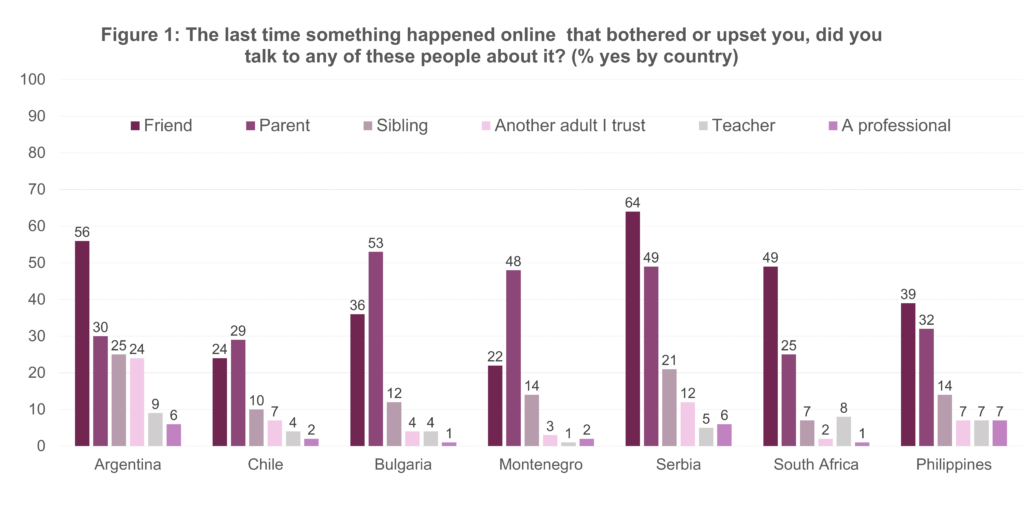

In addition to asking children what they do online, how often and for how long, what skills they have and risks they face, we ask them who they turn to for support if they experience something negative online. Strikingly, the majority of children from the seven countries presented below would turn to friends first, to parents second, and rarely to teachers or other professionals. For parents this is oadly positive news. Although on average, parents’ level of digital skill is equivalent to that of a 14 year old child, as our research from Bulgaria, Montenegro and South Africa shows. What seems to count more is that children trust their parents’ ability to provide guidance and support.

It’s notable that children in European countries are more likely to tell a parent if they experience a problem online, than in other parts of the world. Perhaps this reflects a more encouraging emphasis on enabling rather than restriction among European parents. Certainly it suggest the need for greater investment in support and guidance of parents in the global South. More worrying is children’s apparent lack of trust in teachers and professionals. This makes us wonder if they are even available to children to the degree we would want them to be, and further, how confident children may be that these professionals are able to provide the right advice.

Note: 9-17 year olds in all countries except 13-17 year olds in Argentina. Also, samples in Serbia and the Philippines were small pilot surveys; in South Africa a convenience sample was used; in all other countries, the sample is nationally representative. For more methodological details, see www.globalkidsonline.net/results

How to support parents to support children?

If parents’ primary method of protecting children is through restricting access, this can be effective in keeping children safe, but it carries costs as regards children’s opportunities online. The restrictive approach can potentially undermine children’s opportunity to build digital skills and resilience in ways that will help them face and manage risky experiences in the future. So what advice can we give parents? What are the roles and skills they need to have in the digital world? Do parenting principles and practices we used before the technological boom still apply?

In 2007 the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a framework that examines key dimensions of parenting and parental roles that positively affect adolescent well-being:

- Connection (building a positive, stable, emotional bond between parent and child)

- Behaviour control (including supervision and guidance of children’s actions within a trusting relationship)

- Respect for individuality of the child, especially as an adolescent

- Modelling appropriate behaviour (since children identify with and emulate their parents)

- Provision and protection (by parents and also the wider community)

Ten years on, this framework translates well in the digital era. Take modelling of appropriate behaviour, for example. If the parent does not put down a phone or a tablet, will the child mimic this behaviour? If a parent uses restrictive mediation and censorship, how does this lead to respect for individuality? Ideally, parents would be confident in drawing on their available personal and cultural resources and, to some extent, the principles of positive parenting, when facing the new challenges linked to children’s internet use. Ideally, too, even if tempted to prevent or restrict children’s digital activities for fear of the harms that may result, they would be mindful that some activities may be important to their children’s present and future opportunities – to learn, gain information, work and engage in their community. So a balance must be sought, and this is indeed difficult to manage, for much will depend on the child and his or her particular circumstances.

However, as internet use becomes more familiar, and more embedded in everyday life, parents are increasingly also digital natives. They often want to learn about the internet and what it can offer, for the benefit of themselves and their children. It is therefore important that stakeholders – from government and industry to schools and communities – make greater investments to aid parents in this effort, so that they can enable their children to learn and grow in the digital age.

- For more on parenting in relation to digital media.

- For more on Global Kids Online’s findings around the world.

- For more on children’s rights and wellbeing in the digital age, see State of the World’s Children 2017