UNICEF releases the 2014 Children in China: An Atlas of Social Indicators New data highlights how regional disparities and migration impact on children’s rights

2015-01-13

| BEIJING/ HONG KONG, 13 January 2015 - With its spectacular economic development, China is scoring well nationally on many social indicators for children and has already achieved many of the Millennium Development Goals. Yet striking geographical disparities, along with the impact of migration, continue to pose challenges to the survival, development and protection of millions of rural and vulnerable children according to Children in China: An Atlas of Social Indicators 2014. The newly released Atlas, first inaugurated in 2010 and jointly compiled by UNICEF, the National Working Committee on Children and Women (NWCCW) under the State Council and the National Bureau of Statistics, provides a statistical overview of the situation of children in China. |

|

© 2011/Tang Xiaoping |

“We hope that this Atlas can serve as a reference for the Government and relevant institutions in monitoring and evaluating child development status, in working towards the goals of the National Programme of Action for Children, in promoting child development and protecting the rights of children,” said Su Fengjie, Deputy Director of the NWCCW’s Executive Office. “We also hope that this Atlas, in drawing attention to China’s significant achievements for children, will raise public awareness and support for children. According to the latest figures, China, with an estimated 274 million children in 2013, has made remarkable achievements in poverty alleviation, ensuring universal access to primary education, promoting gender equality and reducing child mortality. China’s national under-five mortality rate, for example, declined, from 61 per thousand live births in 1991 to 12 per thousand live births in 2013, with an average annual reduction of 7 per cent. |

In 2013, China’s under-five mortality rate was 1.4 times higher in rural areas than urban areas, while infant mortality rate was 1.2 times higher and neonatal mortality rate 1 time higher, indicating a gap between survival rates. In general, although there are some exceptions, regions with a low GDP per capita have a relatively high child mortality rate, and vice-versa. In Beijing, the under-five mortality rate is less than four per thousand live births in 2013, while in Xinjiang and Tibet, it is around 25 per thousand live births.

Figure 1 Under-five mortality rate, 1991–2013 |

“In-country disparities mean that development outcomes for children and women in the poor rural areas of China are similar to those in low-income countries,” said Mellsop. “In cities, migration and rapid urbanization present additional challenges related to urban poverty and vulnerability.”

|

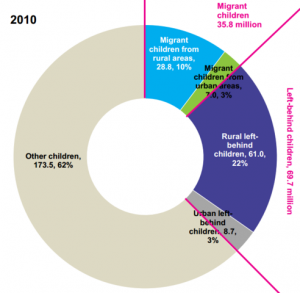

The Atlas indicates that the number of children affected by migration dramatically increased from 42.72 million in 2000 to 106 million in 2010, which accounted for 38 per cent of the total child population in China. Among them, 35.81 million children migrated with their parents to urban areas, while nearly 70 million were left behind, mostly in rural areas. In 2010, one out of every four children in China’s urban areas was a migrant child. Many children face hardship and discrimination in their new environment, and are not registered in their new place of residence and their public service needs remain “invisible” to the local authorities. |

Figure 2 Children affected by migration as a percentage of all children, 2010 |

For those rural left-behind children, who accounted for 40 per cent of all rural children in 2010, surveys suggest most of them maintain irregular and limited contact with their parents and feel lonely, isolated and deprived of support, which has a negative impact on their physical, educational and psychosocial development and well-being.

The Atlas also highlighted that left-behind children are more prone to be exposed to the risks of trafficking and accidental death.

| “We welcome the Government of China’s commitment to address inequalities and to make sure the benefits of economic growth and development reach the most vulnerable children,” said Mellsop. “Many reforms have been introduced to achieve these goals. However, the sheer scale and complexity of the challenge means that progress is gradual. UNICEF looks forward to continued collaboration with the Government to reach children everywhere and make sure they have their fundamental rights met.” Other key findings in the report: • China had the world’s second largest child population (aged 0-17 years), with an estimated 274 million children in 2013, representing 20 per cent of China’s total population and 14 per cent of the world’s children. However, the number of children in China declined by 21 per cent between 2000 and 2013. |

© UNICEF China/2010/Jerry Liu |

• The rate of exclusive breastfeeding in China is 28 per cent nationally, with 16 per cent in urban areas and 30 per cent in rural areas(2008 National Health Services Survey).

• In China, it is estimated that over 10 million children under 18 years of age are injured each year, and more than 50,000 children die from drowning, traffic accidents, accidental suffocation, falls, poisoning and other accidents.

• UNICEF and WHO (2014) estimates show that around 470 million people in China did not use improved sanitation facilities in 2012, accounting for 35 per cent of the total population. In rural areas, 44 per cent of people did not use improved sanitation facilities.

• In a 2010 survey among 22,288 young people aged between 15 and 24 years, two-thirds of young people are open to premarital sex, and 22.4 per cent have had sex before marriage. Over half of the young people surveyed had no form of protection in their first sexual encounter.